Contradictory views merit examination of the cooperation between the Templar and Hospitaller military orders buring the Crusades. The rules laid down by the Orders contain much information on their mode of coexistence in the East.

Contradictory views merit examination of the cooperation between the Templar and Hospitaller military orders buring the Crusades. The rules laid down by the Orders contain much information on their mode of coexistence in the East.

During the twelfth century the Frankish navy seems never to have passed an embryonic stage, which compelled the kings of Jerusalem to constantly search for external alliances. There was no direct reason for the Templars to invest in maritime activities in the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe directly after the First Crusade. Their first objective was pacification of the roads of the kingdom of Jerusalem.

"The legislative body by which the friars of the Temple govern themselves underwent many logical adaptations to suit the times, along its existence. In spite of this, they channeled themselves in two different and complimentary but equally valid points: on the one side papal bulls and on the other the general chapters.

"An astonishing enthusiasm was excited throughout Christendom on behalf of the Templars. Princes and nobles, sovereigns and their subjects, vied with each other in heaping gifts and benefits upon them, and scarce a will of importance was made without an article in it in their favour. Many illustrious persons on their deathbeds took the vows, that they might be buried in the habit of the order. And sovereigns, quitting the government of their kingdoms, enrolled themselves amongst the holy fraternity, and bequeathed even their dominions to the Master and the brethren of the Temple.

"(...) During the Crusades, coexistence manifested itself in another way. Richard the Lionheart (king of England, 1189–1199) attempted to arrange a marriage between his sister and the brother of Saladin (the most famous hero of the Counter-Crusade and founder of the Ayyubid Dynasty). Intermarriage between Christians and Muslims was commonplace in Anatolia, and it was quite frequent between the Seljuk Turkish (who had conquered Byzatium in 1071, TN) and Byzantine elite.

"It might be surprising to imagine that the societies of the medieval Mediterranean were brimming with diversity. (...) Linguistic and religious diversity were facts of everyday life throughout the medieval world. And—very much like today—diversity had its share of proponents and its discontents.

As early as the tenth century the situation and dependence of the church on worldly power had alarmed many devout men. In the hope of improving the monastic system William I of Aquitaine, Duke of Aquitaine and count of Mâcon, nicknamed William the Pious, (...) asked the abbot Berno (850-927) of the monastery of Baume, near Besançon, for advice on the foundation of a small new abbey, where twelve monks would enter. This became the abbey of Cluny.

"The fathers of the church were not altogether happy about this new fashion (of 4th century pilgrimage to the Holy Land, TN). Even Jerome, though he recommended a visit to Palestine to his friend Desiderius as an act of faith and declared that his sojourn there enabled him to understand the Scriptures more clearly, confessed that nothing really was missed by a failure to make the pilgrirnage.

In 910 count William I of Aquitaine founded the abbey of Cluny, and in a few decades Cluny became the center of a vast ecclesiastical nexus, closely controlled by the mother-house, which itself owed obedience to the papacy alone. The Cluniacs took an interest in pilgrimage, and soon organized the journey to the Spanish shrines.

"Long before pope Urban II made his ímpassioned plea at Clerrnont, the Italian cities were fighting the Saracens on land and sea.

"At the beginning of the eleventh century France was the only feudal state in Europe. (...) Actually France was not a single state but an alliance of feudal principalities bound together by the feeble suzerainty of the king.

| source |

On the internet, for example on the page of the OSMTH of France, one is preparing to celebrate this year the 900th anniversary of the Knights Templar. This stems from the proposed year of origin 1118 which is nowadays considered false.

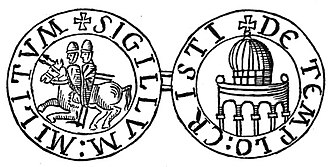

At present it is widely accepted that it was in 1119 that the French knight Hugues de Payens approached King Baldwin II of Jerusalem (crowned king at Bethlehem on Christmas Day 1118) and Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem (installed in August or September 1118), and proposed creating a monastic order for the protection of these pilgrims. King Baldwin and Patriarch Warmund agreed to the request, probably at the Council of Nablus in January 1120. The king granted the Templars a headquarters in a wing of the royal palace on the Temple Mount in the captured Al-Aqsa Mosque.